When Franklin Roosevelt was elected in 1932, public confidence in and support for the nation’s banking system were at an all-time low. Roosevelt’s campaign capitalized on Hoover’s failings and promised a new approach to the economic crisis.

During the banking panics of 1930, 1931, and 1933, the Federal Reserve failed to provide adequate liquidity to struggling banks. This inaction led to numerous bank failures and a significant reduction in the overall money supply as people hoarded gold coins at home.

Just one day after taking office, Roosevelt declared war on ordinary American citizens by referencing an old World War I statute called the “Trading With The Enemy Act” of 1917. He declared a four-day bank holiday and closed all banks, including the Federal Reserve.

A few days later, the Emergency Banking Act was signed into law, which gave Roosevelt unprecedented power and control over the economy.

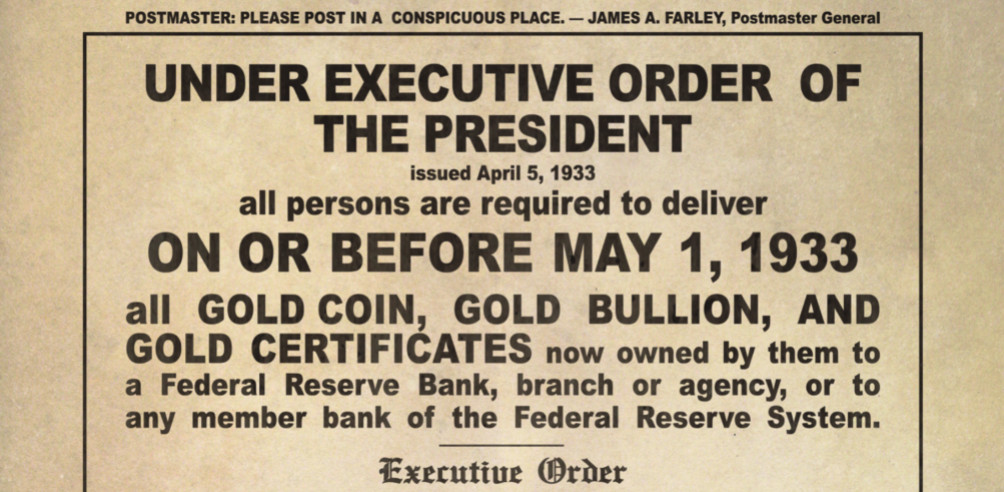

Just a month later, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102 mandating that all American citizens hand over their gold, including bullion, coins, and other forms, to the US Treasury.

Public Response to EO 6102

During his “fireside chats,” Roosevelt portrayed gold confiscation as a patriotic duty, suggesting that citizens should support the government’s efforts to revive the economy.

Under threat of prosecution from the Federal Government, millions of ordinary citizens were forced to hand over their gold or go to jail. In exchange, the government “generously” compensated people at the mandated gold price of $20.67 per ounce.

The executive order immediately ordered the US Mint to destroy all newly minted 1933 gold coins, except twenty coins, which were documented to have been stolen.

Citizens were allowed to keep a nominal amount of gold, up to $100 worth of gold. That was the equivalent of just five $20 St-Gaudens Double Eagle Gold Coins in those days. Today, those five coins are worth more than $12,000.

After the order, the US effectively went off the gold standard and allowed the Federal Reserve to increase the money supply by printing more fiat currency. Just thirty years after establishing the Federal Reserve in 1913, Roosevelt signed over control of the economy to a cartel of bankers who profited from the debt created by the government.

Exceptions to the Gold Confiscation

The exception allowed citizens to own small gold jewelry and up to $100 in gold coins.

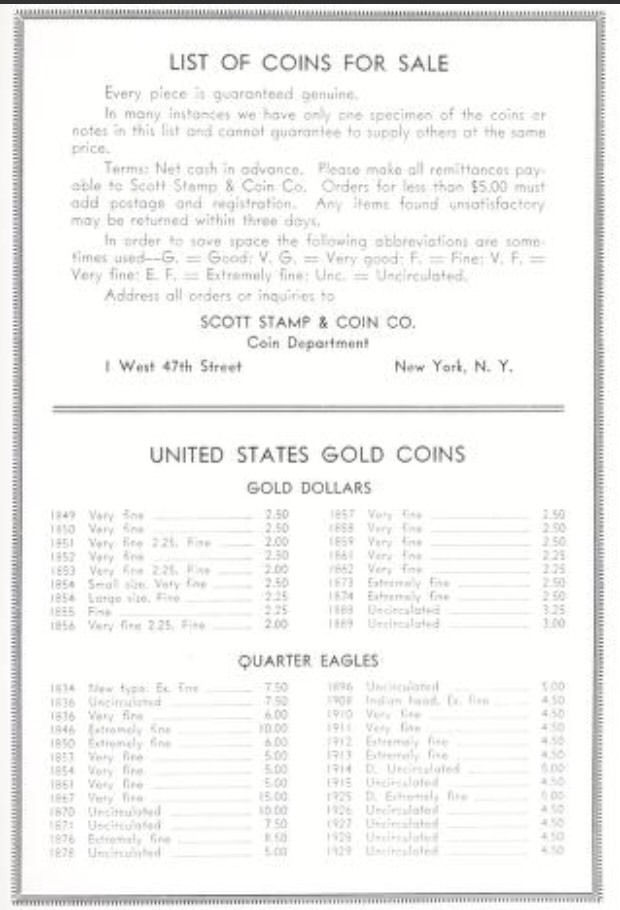

There were exceptions for gold coins, such as collector coins, those with numismatic value, and those that were rare or unusual.

A 1934 issue of The Coin Collector’s Journal featured an advertisement for a local coin shop in New York City that sold uncirculated $2.50 quarter eagle gold coins from the 1920s for $4.50, a 180% premium.

Other denominations show similar premiums due to the dollar’s devaluation, which increased the price of gold from $20 to $35 per ounce.

Many investors looking for the stability of gold became coin collectors practically overnight. In addition to maintaining their intrinsic value today, these gold coins carry cultural heritage and historical significance. Americans during that time understood the actual value of gold.

In today’s market, it is common to find inexpensive Pre-1933 gold coins at bullion prices that may have an added jewelry clasp. This became a common way for citizens to continue to hoard gold. These bullion coins often have lower premiums and can be a cheaper option when compared with graded collectibles.

One of a Kind 1933 Saint-Gauden’s $20 Double Eagle Gold Coin

One of the stolen coins was sold to King Farouk of Egypt. It was lost for decades before being turned over to the FBI by a coin dealer from London named Steven Fenton in 1996.

The one-of-a-kind 1933 Saint-Gauden’s $20 Double Eagle gold coin eventually became legalized. It was first auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2002 and purchased by shoe designer Stuart Weitzman. The coin hit the auction block again in 2021, fetching over $18,000,000.

Legal Challenges Against Executive Order 6102

Executive Order 6102 faced several legal challenges based on its constitutionality and the forced seizure of private gold.

The most notable case is Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co. (1935), which reached the U.S. Supreme Court.

This case and Perry v. United States revolved around gold clauses in contracts. These clauses stipulated that the government was required to repay the bond in gold or the equivalent value of gold coin, which was standard practice in many contracts before 1933.

Perry v. United States involved a U.S. government bond with a gold clause. The bondholder, Mr. Perry, argued that the government had failed to uphold the bond terms by not repaying it in gold, as promised.

After Executive Order 6102, Congress passed the Joint Resolution of June 5, 1933, to address these clauses by declaring them null and void.

The government argued that gold clauses significantly threatened the nation’s recovery efforts during the Great Depression.

Supreme Court Ruling on Executive Order 6102

The Supreme Court agreed that, while the government had technically violated the terms of the contract by not paying in gold, the bondholder had not suffered any actual damages because the bond’s value remained the same in dollars.

The Court upheld the government’s action, ruling that Congress had the constitutional authority to regulate the currency under the Commerce Clause and that abandoning the gold standard was necessary for economic recovery.

This ruling allowed the government to continue printing money without being constrained by the need to redeem it in gold.

Conclusion

The legal challenges to Executive Order 6102 were significant, as they questioned the federal government’s ability to seize private property and regulate the monetary system during an economic emergency. Although these challenges raised valid constitutional concerns, particularly regarding property rights and contractual obligations, the U.S. Supreme Court consistently upheld the government’s actions. The Court’s decisions in cases like Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co. and Perry v. United States solidified the government’s authority to regulate currency, invalidate gold clauses, and move away from the gold standard, ultimately allowing for more flexible monetary policies to support economic recovery.

After Executive Order 6102, the U.S. government invalidated all gold clauses in contracts, effectively making it impossible to demand repayment in gold or its equivalent value. The Supreme Court upheld the government’s action, ruling that Congress had the constitutional authority to regulate the currency under the Commerce Clause and that the abandonment of the gold standard was a necessary measure for economic recovery.

While these challenges did not overturn the executive order, they raised significant questions about the limits of government power during times of economic crisis.